“I believe I’m next” – A Polish Political Assassination’s Echoes in Eastern Europe

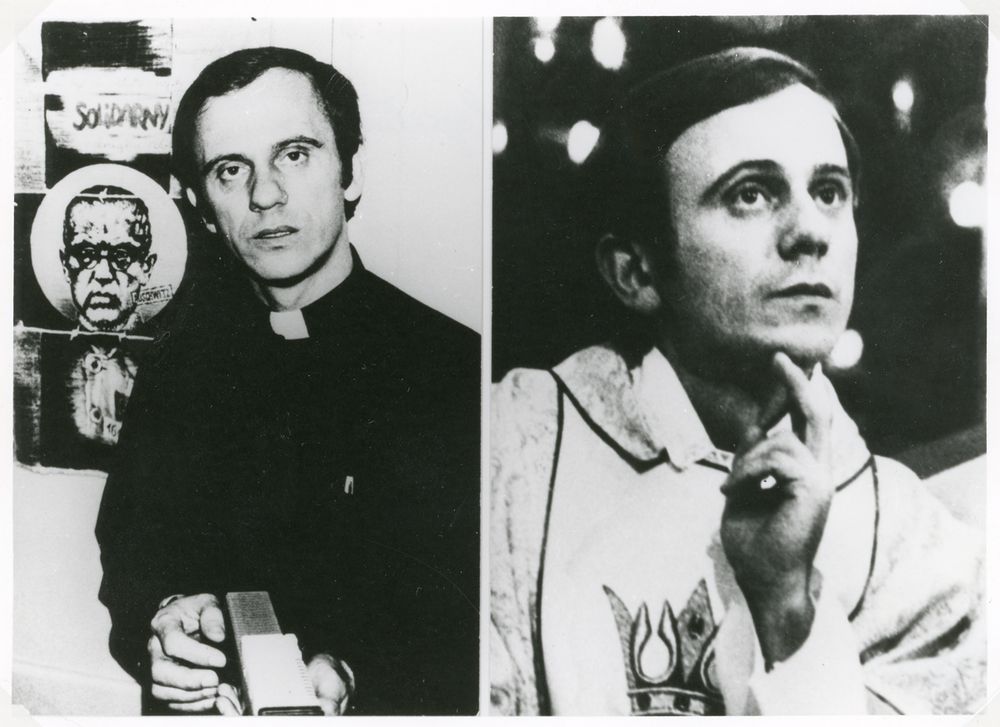

In October 1984, the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute, in Munich, received ominous news from Socialist Poland. The 37-year-old Father Jerzy Popiełuszko, an outspoken supporter and advocate of the underground Solidarity movement, had been kidnapped and taken to an unknown destination. Fears were soon confirmed: 11 days later, the Catholic priest’s body was found in a reservoir. The Polish society, fighting for its freedoms, was shocked; but the case provided opposition groups across the Soviet Bloc with an opportunity to make their voices heard. The death of Jerzy Popiełuszko should therefore be seen not only as a tragic chapter in Polish history, but also as a transnational, shared Central European event, experience, and memory.

Forráspont (Source, or Boiling point) is a blog series by the Blinken OSA Archivum staff at the Hungarian news website 444.hu. Gábor Danyi (literary) historian and translator, reconstructed, as grantee of the CEU Budapest–OSUN postdoctoral fellowship at the Blinken OSA Archivum, how Jerzy Popiełuszko’s figure had become a transnational symbol after his death. The post originally appeared on osaarchivum.444.hu, on the 39th anniversary the priest’s murder.

The rather conservative Popiełuszko was by no means one of the unknown victims of the regime. At the St. Stanislaus Kostka Church in Warsaw, the masses he celebrated for the “Motherland” attracted crowds, he was actively involved in helping the imprisoned and interned, as well as their families, and he offered spiritual support to the hapless. Instead of an institutional hierarchy, he considered the Church a community formed by Polish society. He believed that the Church’s destiny was one with that of society, inseparable from it. It is not surprising, therefore, that he himself stood for the same values the Solidarity movement was fighting for: self-government, the right to strike, non-violence, the reduction of state repression, freedom of the press, and social solidarity. He did not back down even when, under state security pressure, it became increasingly clear that his life was at stake. When in the spring of 1983, militia men beat a young man, Grzegorz Przemyk, to death in Warsaw, Popiełuszko allegedly said, “I believe I’m next!”

For many months, his assassination kept the public busy in Poland and in the West, while the state press in Eastern Bloc countries mostly remained quiet, or repeated the distorted narrative of official Polish propaganda, disclaiming responsibility. The murder of the Polish priest played a major role in maintaining the events in Poland—above all, the activities of the societal resistance spearheaded by the Solidarity movement—an international media event. The New York Times, for example, carried 10 front-page pieces on the case; this sustained media attention was also due to the gradually unfolding details and the crime thriller-like nature of the story.

News of Popiełuszko’s abduction first surfaced on October 19, 1984; at that time, it was unclear if the priest was alive or not. Religious believers and Solidarity activists kept vigil and prayed in crowds for his safe return. Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa said that if a hair on the priest’s head was harmed, someone would have to take responsibility. Many church and social organizations condemned the kidnapping, as well as the Communist government itself, striving to avoid any fallout from the incident. However, Popiełuszko’s driver managed to flee the scene, and his testimony revealed the identity of the perpetrators: Interior Minister Kiszczak was forced to admit that Captain Grzegorz Piotrowski and two of his subordinates, Leszek Pękala and Waldemar Chmielewski, had committed the kidnapping. On October 30, those still hopeful were shocked to learn that divers had found Popiełuszko’s body in a reservoir near Wocławek, a town in eastern Poland. Nowadays it seems like a horrible joke that at 2 p.m. the next day, the authorities announced the expulsion of Popiełuszko’s three suspected murderers from the Communist Party. The results of the autopsy were not made public, as it was considered that the violent details would only further upset the public; the state security officers had locked the priest in the boot of a car, repeatedly beaten and strangled him, and then dumped his body into a branch of the Vistula.

At the same time, however, photos of the priest’s corpse began to circulate in the Polish underground press, uncovering the brutality of the murder—the state media insisted that the lesions had only occurred after death. The photos found their way into Western newspapers, and from there back to other Socialist countries. Media attention was further heightened by the start of the killers’ trial in Toruń on December 14, 1984, at the end of which Piotrowski and his superior, Adam Pietruszka, received 25-25, Pękala 15, and Chmielewski 14 years in prison. In the following years, however, their sentences were commuted several times, so that eventually they only served a fraction of the original punishment. The traces leading to upper circles have never been proven.

For Polish society, the murder was significant and symbolic in several aspects. On the one hand, it exposed the lies and repressive nature of Polish “normalization,” i.e., the military dictatorship General Jaruzelski had imposed in December 1981. On the other hand, Father Popiełuszko in one person stood for other victims—known or unknown—of the regime. His death could represent the murders committed by the police and the military during the “pacification” of the December 1970 riots or the 1981 strikes at the Wujek mine; but it also may have brought to mind those who had been interned or imprisoned since the martial law.

In an interview, Lech Wałęsa called the death of the Polish priest “the biggest shock since the martial law of December 13, 1981.” The incident also galvanized Solidarity—paralyzed since the martial law had been imposed a year and a half ago—and gave the organization an opportunity to demonstrate its strength. Although there were debates within Solidarity on how the mass movement should react to the news of the murder, in the end, a scenario of silent commemoration and calls for dialogue prevailed over that of open street demonstrations, strikes, and confrontation. This was in line with Popiełuszko’s aspirational views for conversation; in his last mass, for example, he prayed, “Let us pray to be freed from fear, from intimidation, but above all from the spirit of revenge and violence.”

It is not an exaggeration to say that a spontaneous religious cult developed around Popiełuszko after his death. His funeral on November 3, 1984, was attended by hundreds of thousands of people. Ákos Engelmayer, a Hungarian living near Warsaw, hung a Hungarian solidarity banner on the parish fence with the inscription “Hungarians in solidarity in pain.” In the years that followed, Popiełuszko’s grave became a pilgrimage site visited by an estimated two million people by March 1987, including private individuals, delegations, Western politicians, and dissidents from behind the Iron Curtain. At the same time, memorials were erected throughout Poland and among the Polish diaspora (in Chicago, for instance), and the place of his murder was marked with a cross. Year after year, memorial services were held on the anniversary of his death, joined by tens of thousands of people. The cult was greatly influenced by Pope John Paul II’s regular reminders of Popiełuszko’s martyrdom.

Shortly after his death, people began collecting materials related to him. His proclamations were distributed hand to hand on unofficial cassette copies, and were featured on Radio Free Europe’s Polish broadcast, along with recordings of the memorial services. The Solidarity movement issued underground stamps, postcards, leaflets, calendars, and banknotes dedicated to Popiełuszko. The 1980s saw theatrical, literary, and film adaptations of his life and death; a play based on the Popiełuszko trial was staged in London and broadcast on television, and Polish film director Agnieszka Holland made a political thriller in France titled To Kill a Priest; English-language biographies of the Polish priest became bestsellers. Popiełuszko’s death, however, had its impact not only in Poland and the West, but also among dissidents in Eastern Europe.

The death of a Polish Catholic priest was a major event for dissidents in the Soviet Bloc as well. The Czechoslovak human rights movement Charter 77, for example, quickly declared the case an act of terrorism in a statement of solidarity, indicating that the traces were leading upwards. They also noted that Popiełuszko’s death strengthened the Catholic Church and Polish Solidarity. A similar statement was issued by the editorial staff of Beszélő (Speaker), the most prominent political samizdat journal in Hungary (modelled, by the way, on Polish underground practices). In addition to condemning the political crime committed with “savage cruelty,” they drew attention to the fact that the power of the police and the number of offences was increasing in Hungary as well. “After Popiełuszko’s martyrdom, no one in this part of the world can any longer claim that they did not know what giving the police a free hand to violate human rights would lead to,” the statement concluded.

The democratic opposition in Hungary sent a message to the community of the St. Stanislaus Kostka Church. The open letter, signed by a total of 43 Hungarian intellectuals, workers, and students (including Miklós Haraszti, Róza Hodosán, János Kis, György Krassó, and Ottilia Solt), made the death of the Polish priest an issue of Eastern European importance: “After his brutal murder, Father Jerzy Popiełuszko is mourned not only by his relatives, fellow citizens, supporters, and Solidarity followers; his martyrdom was for all of us, Eastern Europeans. He died for the elementary rights for which we now continue to fight without him.” The open letter was published in the underground periodicals Külön-Beszélő (Separate speaker) and Hírmondó (Herald), and even in Polish translation in the Polish samizdat newspaper Obóz (Camp).

Meanwhile, the cult of Popiełuszko also spread in small Catholic communities in Hungary. From the early 1980s, hundreds of young Catholics joined pilgrimages to Poland, where they learned about Popiełuszko’s activities and teachings through pamphlets and cassettes. Many of them also attended the memorial masses on the anniversaries of the martyr priest’s death. One of these Hungarians was a young man studying in Szeged, Imre Molnár, who smuggled numerous Popiełuszko-related documents into Hungary, including material from an unofficial exhibition, and published, with the help of others, an illegal Popiełuszko memorial book in a small print run.

The Inconnu Art Group, a radical artist collective associated with the democratic opposition, was also involved in commemorating the Polish priest. In December 1984, the group organized an exhibition of their own work at the Artéria Gallery, which was housed in a private apartment in Budapest. Here too, the Popiełuszko murder and its memory were incorporated into the general struggle for freedoms in Eastern Europe. State security reports pointed out that, in addition to tableaus, there were several “object-like works” in the exhibition; for example, a white chair was painted with the inscription “I am also Popiełuszko” in black paint, suggesting an Eastern European common destiny, while a first-aid kit filled with syringes was marked “Freedom for Duray,” raising awareness of the imprisonment and forced medical treatment of Miklós Duray, a defender of the rights of the Hungarian minority in Czechoslovakia. A few months later, in January 1985, the Inconnu Group organized an exhibition in memory of Popiełuszko. The exhibition presented some 25–30 photographs of the Polish priest’s funeral on a dozen panels. At the vernissage, Popiełuszko’s last sermon was read out, the text of which was available for purchase on the spot, and an audio recording of which could be ordered on cassette.

Nine months later, on October 20, 1985, on the anniversary of the Polish priest’s death, the group organized another commemorative exhibition. According to state security documents, this time around a hundred photographs, mostly taken at Popiełuszko’s funeral, were put on display. The aforementioned Imre Molnár took an active part, playing excerpts from recordings of masses celebrated by the Polish priest. Later, Géza Buda published an article in the Inconnu Group’s samizdat periodical, writing, “The martyrs of the Eastern European revolution, which has been smoldering for 30 years, are growing in number. The names of Imre Nagy, Jan Palach, Jerzy Popiełuszko symbolize the people’s movements that have been trampled into the ground, the thousands of victims, the burnt hopes of nations.” It is noteworthy that in these lines the author has juxtaposed the martyrs of the Hungarian, Czech(oslovak), and Polish recent past, suggesting that they are all martyrs of a common Eastern European civil rights struggle.

Apparently, the memory and cult of Popiełuszko has spread far beyond the borders of Poland, thanks to the dissidents from Eastern Europe, including Hungary. In the process, the emphasis shifted, and the martyrdom of the Polish priest became an event of Eastern European significance. And not without reason: the case of Popiełuszko shows that during the final one and a half decade in the history of Communism in Eastern Europe, dissidents in the Soviet Bloc were mutually attentive to each other and strived to coordinate their activities, which they imagined as part of a joint, united Eastern European fight against repressive regimes.